In the increasingly complicated war against antisemitism, in which there are many front lines and so many ways of fighting hate, a critical question is “Where do we invest time and energy that will make the most difference?” Many activities against antisemitism can have an impact, but in a war this important, how do we ensure we’re spending time on what is proven to work? As William Dean Howells said, “An acre of performance is worth a whole world of promise.”

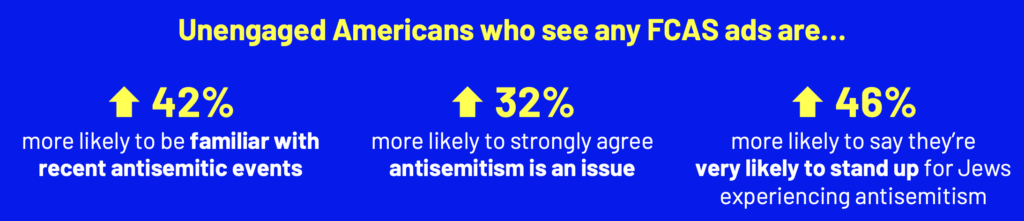

These questions have driven The Foundation to Combat Antisemitism (FCAS) since our founding in 2019. Our focus on impact is relentless, guided by data and research that inform our strategy and execution and measure our impact. The result of this hard work is clear: When our target audience sees any of our ads, they are 32% more likely to strongly agree that antisemitism is an issue and 46% more likely to stand up for Jewish people experiencing it.

We believe that what we’ve learned along the way about what works is useful not only to us, but to anyone fighting antisemitism. And so we’ve assembled these key findings from our research and testing in the hopes that they help others in their own important work.

We are not our target audience

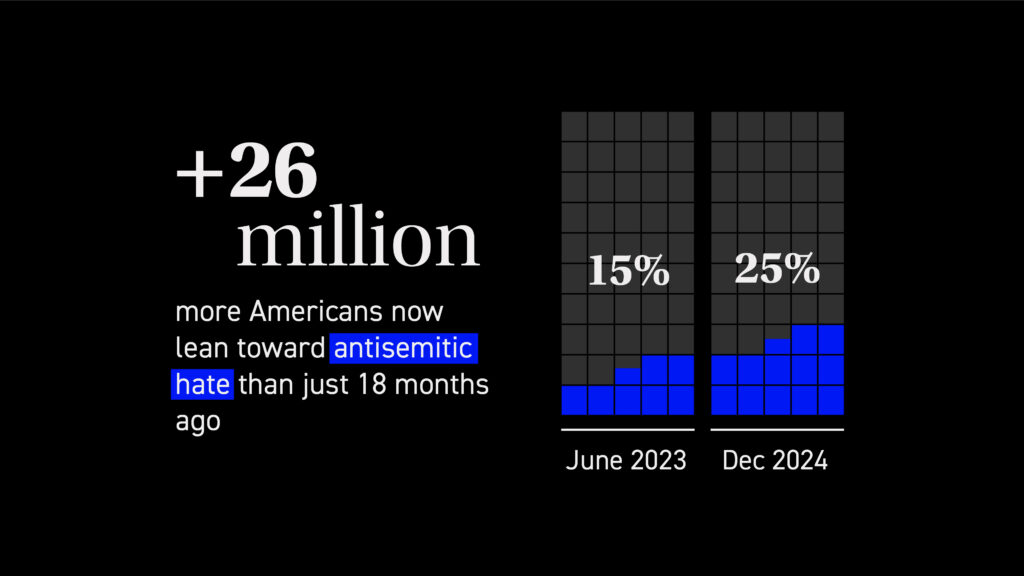

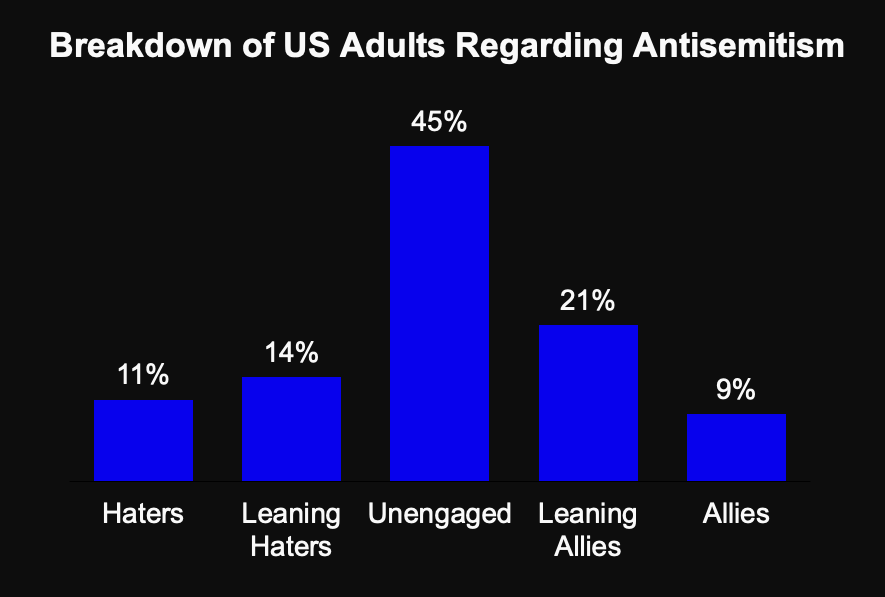

Any strategy focused on impact begins with agreement on the target audience of the desired impact. At FCAS, our focus has always been on the 45% of US adults who are Unengaged on the topic of antisemitism.

Instead of focusing on activating Allies or exposing Haters, we spend most of our energy reaching Unengaged Americans and moving them to Allies. (For more information on our approach to segmentation and the trends with these groups over time, see our report on the latest survey findings.)

Everything we do is driven by a deep understanding of Unengaged Americans, so we can make decisions based on what they will respond to, not just what resonates with ourselves. The FCAS team is obviously not Unengaged Americans; messaging that works on us doesn’t necessarily work on them. So all the research and testing we do is focused on this specific audience—nationwide surveys, focus group studies, ad testing, and so on.

Applying the Theory of Reasoned Action to antisemitism

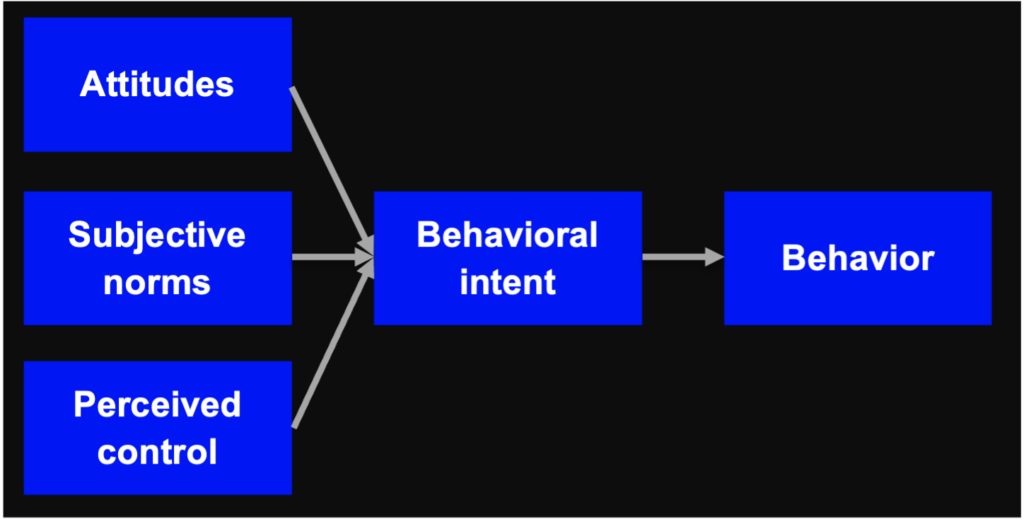

To understand our target audience, we have found the Theory of Reasoned Action particularly useful for identifying the journey that we need to create for moving Unengaged Americans to Allies. This theory, later extended as the Theory of Planned Behavior, is a psychological model to help us better understand human behavior—in particular, what drives persuasion and then behavior.

In a nutshell, this framework posits that any attempt to change minds and encourage behavior (e.g., stand up to antisemitism) must include these elements:

- Understand a person’s current attitudes around a topic and influence them toward a belief that a specific behavior will lead to outcomes they value.

- Recognize that each person is influenced by what they think people in their lives would want them to do. Subjective norms are the perceived peer pressure surrounding any behavior change.

- Amplify a person’s perceived control: Persuade them that they have the ability to act in a way that can make a difference.

All three of these factors are influenced by the external context of a person’s background—e.g., personal experiences, existing attitudes, demographic influences, and personality traits.

The central point is this: We can’t drive change in a person without first understanding (and influencing) all the factors that live upstream.

How does this apply to guiding an Unengaged adult down the path to allyship? Let’s look at what we know from FCAS research in each area.

External context: It’s easy to forget how unaware many Americans are

To engage with Unengaged Americans, we must start by walking in their shoes and tackle basic awareness. Our research constantly reminds us that for millions of Americans, Jewish people and antisemitism are simply not part of their lives and not something they think about. Our December 2024 survey of 8,000 US adults showed that 42% of Unengaged Americans say they don’t know any Jews. For those that do, Jews are more likely to be acquaintances than close friends or work colleagues.

Given the lower exposure to Jewish people, it’s not surprising that so many Americans don’t recall seeing antisemitism around them or hearing about it. Only 29% of Unengaged people have ever heard a friend, family member, or colleague say something that felt biased or prejudiced regarding Jewish people. (Almost twice as many say the same about hearing something prejudiced against Black people.) Only 25% recall ever seeing a prejudiced post about Jews on social media.

When asked how familiar they are with recent events in America regarding antisemitism/prejudice against Jewish people, only 13% of Unengaged adults say they are very familiar; almost half are not very or not at all familiar. Similarly, many have not been exposed to the history of systemic prejudice against Jews in the US.

Antisemitism either isn’t visible in their world or they don’t know it when they see it, in contrast to other forms of prejudice. They are more than twice as likely to have conversations with people they know about prejudice against Black people than about prejudice against Jewish people. Out of sight, out of mind.

For FCAS, these data points remind us to ground any messaging to our target audience in this simple truth: Antisemitism is real. No one is going to fight hate until they see that it exists.

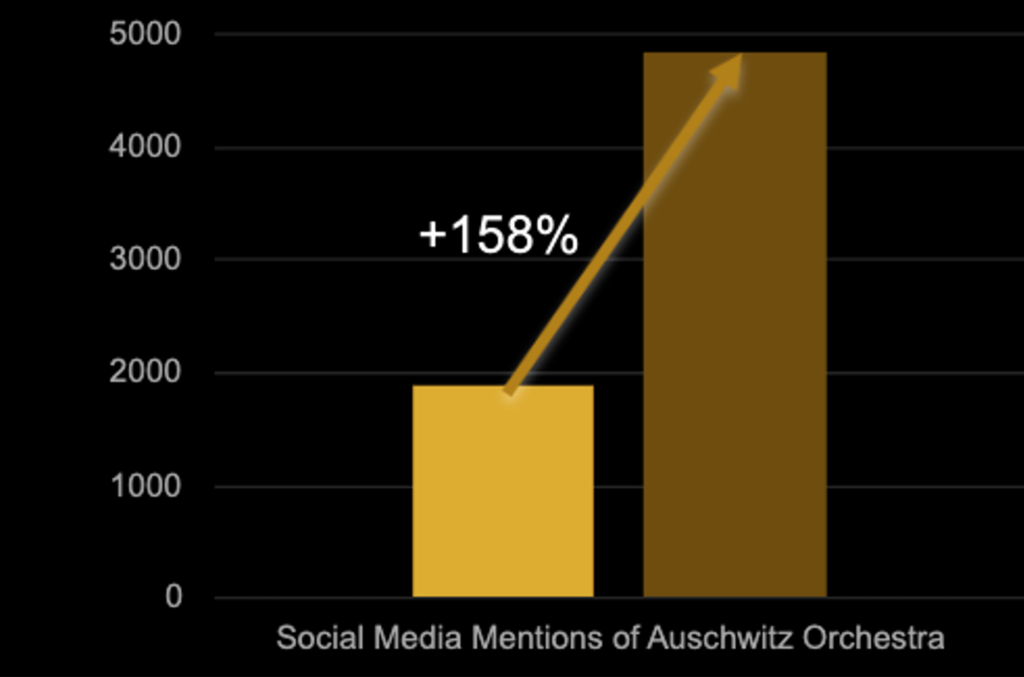

Attitudes: Misinformation often fills a vacuum

In an FCAS focus group research study with Unengaged Gen Z participants in November 2024, one person said something that perfectly summarized a larger trend from our ongoing research: “I don’t really see a lot of Jewish people in my day-to-day life. So, it’s like my conversation with them is whatever people say about them.” When there’s less personal experience with Jewish people and antisemitism, what people rely on is what they hear from others: people they know, posts from random people on social media, depictions in entertainment, and media coverage. Others’ attitudes tend to become their attitudes. Misinformation can take over when accurate information is absent.

Fortunately, there is a path to better education and fighting misinformation that Unengaged Americans are already primed for. Our research has found that almost two-thirds of Unengaged Americans are what we call Social Defenders: People who are aware of and often stand up to other forms of prejudice but fundamentally don’t think of prejudice against Jews the same way. In our survey, 77% believed that prejudice and hate in America were on the rise throughout 2024. However, their attention is far more focused on other prejudice by race, ethnicity, gender, or sexuality. They are 26% more likely to believe racism against Black Americans is a major issue compared to prejudice against Jews.

In the focus group study, we heard repeatedly that in an era of expanding hate, people are going to focus on the prejudice they see themselves, affecting their loved ones. With only so much time and energy to fight hate, people will prioritize what is near them, and that is often not Jewish hate.

Anti-Jewish tropes often feed these attitudes. Unengaged are more likely to believe in insidious stereotypes about Jewish people, and in some cases this unconscious bias gives them excuses to deprioritize antisemitism. 48% of Unengaged adults believe Jews make up a large and influential portion of the US population.

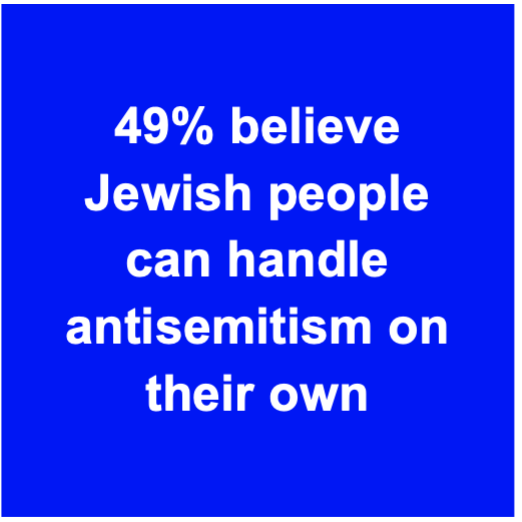

Many believe Jews are generally wealthy and educated. So even if antisemitism exists, 49% believe Jewish people are more than capable of handling it on their own. As one focus group participant said, “They control a majority of everything. So why would they need an ally? Kind of like white males. Do white males need an ally?”

If antisemitism isn’t worthy of the same attention as other forms of prejudice and “positive” tropes further justify ignoring it, no wonder Unengaged Americans are more skeptical about the need to fight antisemitism. 36% even think the issues around antisemitism are “blown out of proportion” in the US. Many think it’s real, they just don’t think it’s as important as other battles against hate.

For FCAS, these findings revealed how critical it is to correct misinformation wherever we find it, and also to put antisemitism in the context of other forms of hate. Messages only about anti-Jewish prejudice are easily dismissed by this group because of their existing attitudes about its importance, developed over many years and influenced by many sources. To break through, we must start by putting antisemitism on the stage with other forms of prejudice: Antisemitism is real. It’s as real as other forms of prejudice. If you say you’re willing to fight hate, fight this too.

Subjective norms: Cultural peer pressure is a headwind

The previous section covered some of the ways in which misinformation from people they know can influence Unengaged Americans’ attitudes around antisemitism. A person’s social networks, online and offline, create self-reinforcing cycles: If my network also has limited exposure to Jewish people and to antisemitism, and they too are prioritizing other forms of prejudice, that pressure can easily deepen my own beliefs.

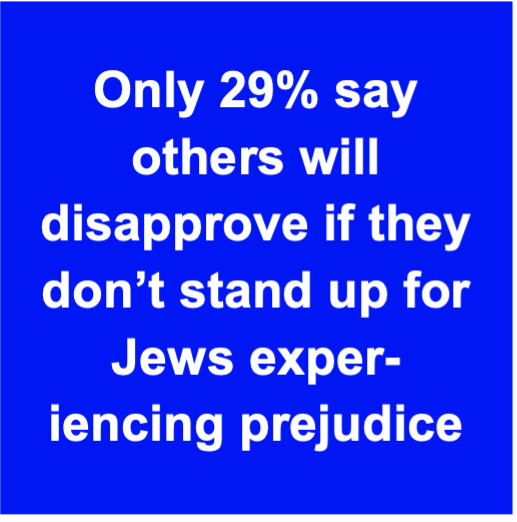

This pattern manifests in our surveys through the following fact: Only 29% of Unengaged people think that others will disapprove of them if they don’t stand up for Jews who are experiencing prejudice. Most are not feeling societal pressure to pay attention to antisemitism; there aren’t many external forces encouraging them to take a fresh look at their assumptions in this area.

The Israel-Hamas war and associated controversy have made this topic even more complicated. For better or for worse, many Americans blur the lines between opposition to Israel’s actions, opposition to Zionist philosophy, and opposition to Jews in general. In many environments, standing up for Jews is seen as standing up for Israel, and in Gallup’s recent survey, Israel’s favorability has now dropped to its lowest level since 2000. Many Unengaged Americans would rather avoid that controversy and complexity and choose to not engage in antisemitism.

For FCAS, knowing that these cultural norms are a real headwind in the fight against antisemitism ensures that we focus not only on changing individual beliefs, but on changing the cultural context as well. It’s another reason that putting anti-Jewish prejudice in the context of other forms of prejudice can make a difference. Our messaging through mass media and social media must create broader cultural permission for informed conversations about antisemitism to occur, so individuals feel they are not on their own: Antisemitism is real. It’s as real as other forms of prejudice. If you say you’re willing to fight hate, fight this too. So many people are already joining this fight.

Perceived control: People assume they can’t make a difference

People can believe that antisemitism is real and serious and be surrounded by cultural forces that encourage instead of discourage standing up against it. But if they don’t believe that as individuals, they can do anything about it and make a real difference, those changed attitudes won’t lead to behavior change. Here, too, we have work to do.

Our December 2024 survey found that a third of Unengaged Americans think there is nothing at all they can do to counteract prejudice against Jewish people. Many others feel they could make little impact. These instincts came to life in our November 2024 focus groups with Unengaged Gen Z, as people described their reluctance to stand up for anti-Jewish prejudice compared to other forms of prejudice that they feel more familiar with:

- “If I think I don’t have a chance of getting through, it’s not worth my time.”

- ”I just think that other people are better qualified. So, I’m putting my energy towards where I feel I am the most qualified to make an impact.”

- “I don’t think I’d go out of my way to necessarily speak up… [it’s like] adding fuel to the fire. I feel like you’re just making it a bigger deal, and for me, I don’t really understand how I could necessarily help.”

For FCAS, this finding has driven our messaging to not only establish the problem but also inspire people with examples of how any individual can make a difference. This isn’t a fight just for large institutions to tackle, it’s a fight for all of us to engage in, especially the Unengaged, who we want to persuade can have an impact: Antisemitism is real. It’s as real as other forms of prejudice. If you say you’re willing to fight hate, fight this too. So many people are already joining this fight. And you can make a real difference. Here’s how.

What research tells us that shifts Unengaged Americans’ attitudes and behavior

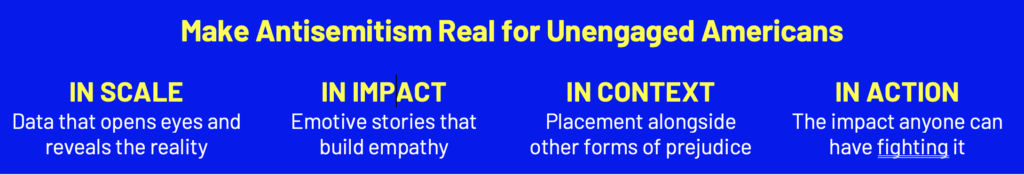

Our ongoing research makes it clear that any campaign around antisemitism that’s targeted at Unengaged adults has to include all these components. Missing a step in the Theory of Reasoned Action leads to a reduction in behavioral intent and also in the behavior of standing up to antisemitism. Here’s how we summarize and activate the ingredients of effective messaging to Unengaged Americans:

We know these ingredients work not only because they address the needs described by the Theory of Reasoned Action, but also because at FCAS we’ve tested these elements over the years with our Unengaged target audience.

Testing our ads

When we test our ads with Americans (through Kantar’s LINK+ methodology), we see how the ads overindex on key attributes that connect to the components above:

- Engagement: The first job in an ad is engaging viewers enough so they pay attention. Even for challenging topics such as antisemitism, the content must be perceived as enjoyable to watch. For us, ads such as Tony and Silence score high in drawing people in (in the 95th and 91st percentile of Kantar’s methodology, respectively).

- Awareness: Once viewers are engaged, driving awareness becomes easier. The Silence ad scored in the 94th percentile in awareness because it places antisemitism in the context of other forms of hate, giving it credibility and weight for those who otherwise had not thought about it in the same category.

- Involvement: Involving viewers is about bringing them into the story and encouraging empathy, often through emotive storytelling. Neighbors, which tells the story of a Christian congregation standing up against Jewish hate, scored in the 94th percentile in this area because it shows how any person and any group can get involved.

- Persuasion: Kantar’s ad testing also provides a diagnosis of how an ad will affect “sales”—or, in our case, a prediction of how it will affect moving people from Unengaged to informed Allies who take action. Our ads consistently score at the 95+ level for persuasion, validating that the way we’re executing on the ingredients listed earlier is having the intended result.

Qualitative research on Unengaged Americans

The findings from our ad testing align with what we have learned in qualitative research, such as the November 2024 focus groups referenced earlier that exposed participants to several FCAS ads. This study revealed two key reasons our ads are having an impact with Unengaged audiences.

Surprising statistics consistently break through with Unengaged Americans. When study participants heard that Jewish people make up 2.4% of the population but are on the receiving end of 60% of religious hate crimes, many responded with statements such as “I had no idea it was that bad.” One participant, after learning of the 895 bomb threats to synagogues last year, realized that if that number had described Christian churches, he’d be “freaking out!” For some people, data was an attention-grabber that brings them into the conversation. For others, data was the evidence they are looking to hear before taking the topic of antisemitism seriously.

Emotional storytelling makes the issue come to life, moving from the head to the heart and creating empathy that drives intent to act. In the focus groups, participants responded positively to the stories of Tony and Neighbors because, as one person said, “I could step into these everyday moments.” They told us the stories felt true and real to them, using average people to model what standing up looks like, communicating that anyone can make a difference. One participant spoke of how the Tony ad created a simple, universal moment of helping another person: “He wasn’t looking for a gold medal for helping somebody who needed it.”

In this research, we saw Unengaged Gen Z respond to these two elements in combination: compelling data alongside powerful true stories, both creating empathy that in turn moved participants toward action.

Message testing from our antisemitism landscape survey

Across multiple nationwide surveys, we ask Unengaged Americans how seeing or hearing specific messages would impact their likelihood to speak up for a Jewish person experiencing prejudice or hate. The results have been consistent, providing quantitative evidence of the key themes that can drive attitudinal change.

Messages that encourage empathy work because they relate the real-life, emotional impact of prejudice. Examples that test well with Unengaged people:

- “If you were experiencing hate simply for who you are, wouldn’t you want someone to stand up for you?” (61% say this would make them somewhat or much more likely to speak up.)

- “Take a second and imagine what prejudice really feels like. Then imagine if it was you experiencing that prejudice.”

- “If I saw someone standing up for someone experiencing hate, I’d feel bad that I didn’t too.”

Messages that include surprising statistics work because they establish the scale of the real problem for people who otherwise have no idea. Examples that test well:

- “Jewish hate is up 388% in the US.”

- “In 2023, more than 1,800 hate crimes were committed against Jews, a 63% increase from 2022.”

- “’Hitler was right’ was posted online 120,000 times last year.”

Messages that connect different forms of hate work because they help people activated on other forms of prejudice see antisemitism in the same light. Examples that test well:

- “Hate is a slippery slope—those who hate one group of people usually hate other groups of people.”

- “When hate rises for one group of people, it starts rising for all groups of people.”

- “Hate feeds violence and gives it permission to grow.”

What people say in a survey about what engages them doesn’t always match reality. But in this case, the themes above from our ongoing survey align with what we observe in ad testing and qualitative research, so these findings guide our work at FCAS.

Overall campaign impacts

Like many organizations, we conduct research to inform our work, we test to validate and iterate, and then we measure overall outcomes to quantify the impact of our strategy and execution. If our version of the Theory of Reasoned Action is correct and we’re using the messaging ingredients effectively, we should see measurable impact.

One way we measure the FCAS campaign’s impact is to track how people who recall seeing our ads are different from those who don’t recall our ads. If people who see our ads are more likely to think or behave in ways we want, those are clear signals of impact and encourage us to double-down on those approaches.

From the start of our ad campaign in Spring 2023, we have seen such impacts across three key measures:

- Familiarity with antisemitism

- Recognition that it’s an issue

- Likelihood to stand up for someone experiencing it

Based on the Dec 2024 survey. Note: These correlations suggest but do not definitively prove causation in ad impacts.

These signals of impact hold up over time across different ads, including some ads focused on Jewish hate and some ads that place antisemitism in the context of other forms of hate.

Like other kinds of mass media campaigns, frequency drives impact. Our research shows that Unengaged Americans who see two or more of our ads are far more likely to agree with the statements above than those who see just one of our ads. For example, Unengaged people who saw one ad are 19% more likely to stand up than those who recall no ads. But those who saw two or more ads are 77% more likely to stand up.

For FCAS, all the research about our target audience that led to our messaging strategy was indispensable to this success. Any one number can’t provide definitive answers or tell the full story, but a suite of approaches to research and testing are vital for ensuring we spend our time and energy on work that makes a difference. We share all these findings from our research because this battle is too big for any one organization to fight it alone. There are many front lines and there’s no time to waste on theories with no research behind them or approaches with no evidence of impact. We hope sharing what we’ve learned can help others expand their impact, and we encourage others to do the same so we can learn from you as well.

Research Studies

| The findings shared here have been gathered from a number of FCAS studies: “Stand Up to Jewish Hate: The US Antisemitism Landscape Survey” is semiannual research on Americans 18 and older conducted by the Foundation to Combat Antisemitism and VML. This ongoing study tracks Americans’ attitudes and actions around antisemitism in the context of recent events. The latest survey, fielded Dec 2024 – Jan 2025, used a nationally representative sample of 8,000 US adults plus an augment of 600 respondents for demographic analysis, weighted to match the US population. Participants are classified into segments (e.g., Allies) based on a weighted scoring methodology applied to a set of attitudinal questions about Jewish people and about antisemitism. The survey was conducted online and has a margin of error of ±0.92%. The focus group study referenced above was conducted with Unengaged Gen Z participants in November 2024. 33 participants joined six two-hour online focus groups, structured by age, race/ethnicity, and university status. The study was conducted in partnership with Research Narrative and focused on beliefs and behaviors around anti-Jewish prejudice and other forms of prejudice, as well responses to FCAS messaging and ads. FCAS tests concepts and ads using Kantar’s LINK+ methodology, enabling rapid, iterative testing typically with 150 participants. The approach combines validated ad effectiveness metrics with predictive modeling and global norms. |

About FCAS

The Foundation to Combat Antisemitism was founded in 2019 by Robert Kraft to stand up to Jewish hate and all hate. We uniquely reach unengaged non-Jewish Americans, moving them to become allies through empathy-building national mass media and social advertising. We partner and convene diverse leaders and groups to create awareness and understanding, and our Command Center monitors the digital landscape 24/7 to understand where and how hate is spreading and completes national research on this topic.

For more information about this research, email us at [email protected]